We visited New York recently and on the advice of JRC walked the Brooklyn Bridge at dusk. The experience inspired me to pick up David McCullough’s book The Great Bridge. McCullough, who won a Pulitzer for his biography of Truman and whose book about the Adams was a best-seller, knows how to tell a story.

The book’s heroes are John and Washington Roebling, the father and son who oversaw the design and construction of the bridge. When John died from lockjaw after a job injury, Washington took his position of Chief Engineer and saw the bridge to completion. But mostly from a distance; he ruined his health working in the caissons during the first stages of the construction.

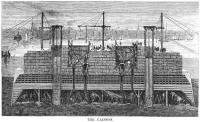

While the bridge’s towers attract attention today (as they did at its completion in 1883, when at 280 feet they dominated the New York skyline), I think the most dramatic part of the bridge’s construction was hidden from view, in the giant caissons beneath them.

Imagine flipping a cake pan upside-down and pushing it underwater. It could hold a pocket of air inside of it, so that if you held it against a river bed, inside the cake pan the dirt would be “dry.” Enlarge that cake pan so that it’s the size of four tennis courts, and make it out of wood plated with metal, and you have the Brooklyn Bridge caissons. Men inside the caisson dug away at the river bed, and as they sunk lower into the earth beneath the river the towers rose on its back.

The problem is that the deeper one goes underwater, the greater the water pressure. And the only thing keeping the water out of the caisson was the air inside; the air also was chiefly responsible for keeping the caisson itself from being crushed by the tons of masonry above it. So Roebling increased the air pressure the lower the men dug, producing some interesting effects. The men could shovel debris underneath a shaft leading to the surface, and the air would blast rocks and sand up and out of the caisson, like a giant vacuum cleaner. Fire was a greater risk, so that after battling for hours one bit of flame that worked itself deep into the planks of the caisson, Roebling gave up and had the structure flooded with water. While in the caissons, workmen’s voices became higher-pitched, and they couldn’t compress their lungs enough to blow out a candle. And some, after returning to the surface, began experiencing excruciating pains they called “Grecian bends” or “caisson disease”–what today we usually term “decompression sickness.”

The technology necessary to produce caisson disease on a large scale hadn’t existed until recently before Roebling built the Brooklyn Bridge, so little was known about its causes and its treatments. Shortly before and during the Brooklyn Bridge’s construction, caisson disease caused the deaths of a number of men working on the Eads Bridge over the Mississippi. Roebling had even visited the caissons for the Eads Bridge to compare them to his plans, but Eads was equally in the dark about decompression sickness.

From the hindsight of history, it’s almost painful to watch Andrew H. Smith, the physician for the construction workers, try to figure out how to treat the malady. He was correct that symptoms worsened the longer one spent in compressed air, so he had the men take shorter shifts. He suspected that it was important how long one took to decompress, but his prescribed time of a few minutes was insufficient (it needed to be about 20 minutes), and the men, impatient to head to the pubs and leave behind the disagreeable caisson work, probably didn’t even heed that amount of time.

When Roebling decided to halt the descent of the New York caisson at seventy-eight feet even though it hadn’t yet reached bedrock, his decision was influenced in part by his concern that caisson disease not kill numerous workers. And he had already begun to suffer from terrible bouts of the bends himself.

Already [physician Andrew H.] Smith had recorded more cases of the bends than Jaminet had in St. Louis. And whereas Eads had not suffered a single fatality until his first caisson was down ninety-four feet and the pressure was at forty-four pounds, Roebling, for some unknown reason, had already lost two men. So at this rate the New York caisson might take even more lives than the thirteen the St. Louis foundations had cost by the time they were in place.

The rest of the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge makes for fascinating reading as well. Roebling, his health broken by caisson sickness, supervised the construction from afar (and only crossed the bridge himself after it had already been open for a while), while dealing with the machinations of various politicians. But the bridge opened to almost unimaginable fanfare: after a day filled with speeches and parties (the President was Guest of Honor), a non-stop fireworks show lasted for an hour.

In another time and in what would seem another world, on a day when two young men were walking on the moon, a very old woman on Long Island would tell reporters that the public excitement over the feat was not so much compared to what she had seen “on the day they opened the Brooklyn Bridge.”

One Comment

So many interesting books, so little time…

The Brooklyn Bridge is an awe-insiring structure, especially when you think of the time period it was built in. Glad that your visit inspired you to read up on it. I may have to check out that book, too.